Communion and Social Justice, or, How the Flesh and Blood of Jesus Turn Our Faces Toward the Reformation of Society: A Lay History of a Baptist Giant (Part 3)

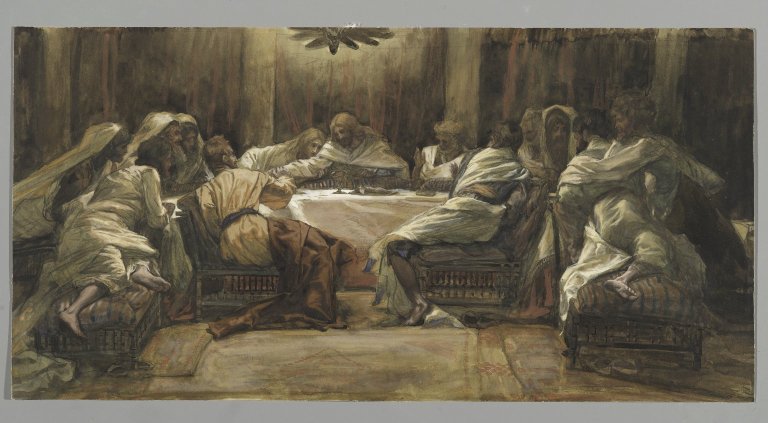

Last Supper by James Tissot, between 1886 and 1894.

With a cursory understanding of the backdrop against which the ‘prince of preachers’ conducted his ministry in place, we can make real sense of him. In Spurgeon’s estimation, the established Church in England at the time could be generally characterized as lacking active communion with God – with the notable exception of the fairly small evangelical subsector therein. This was most clearly visible in what he considered to be the dry, mechanical way in which they went about celebrating the ordinance of Communion. He abhorred their practice of reciting pre-written prayers and carrying out elaborate rituals in tandem with the sharing of bread and wine. He once posed the rhetorical question, “can anyone see the slightest resemblance between the Master’s sitting down with the twelve, and the mass of the Roman community?” referring to the Catholic Mass, he appears to have held the same complaint against the ‘tractarians’ and nominalists in the Church of England.

Evangelical churches, as mentioned earlier, had gradually surrendered their identities as the movement lost cultural influence, leaving London in an awkward position. On the one hand, there was a Christless community of ‘whitewashed tombs’; on the other, a lukewarm community who possessed the gospel but were increasingly without unction. The struggles that Victorian Evangelicals were facing were not, in Spurgeon’s mind, because God was not in their midst. He was of the opinion that God had temporarily withdrawn His Spirit from London, and that He was preparing to stir up a revival unlike anything that had been previously seen. But He had no illusions that revival would come about as the result of innovative ministry methods or captivating preaching styles, although he eventually put both to use in service of the kingdom. Spurgeon’s vision for revival was centered on individuals experiencing radical spiritual awakening through communion with God.

This, for Spurgeon, was what Stanley Grenz calls an integrative motif. It is defined as “that concept which serves as the central organizational feature of the [theological] system, that theme around which the systematic theology is structured.” He explains that it is “the heart of the theological system [and] it focuses the issues discussed and illumines the formulations of our responses to these issues.” To name an example, although Martin Luther never produced a volume specially devoted to systematic theology, justification by faith can be clearly identified as the integrative motif in his framework. Likewise, the entire body of John Calvin’s work is oriented around the glory of God and is best understood when read with that motif in view. Friedrich Schleiermacher, to name one more, theologized around the integrative motif of human religious experience. Reading through Spurgeon’s voluminous writings, it becomes clear that experiencing ‘communion with Christ and His people’ was the heart of his theology. Everything that he said and did—his whole body of preaching, his public prayers, his social concern—was born out of that integrative motif.

His theology, then, was a breath of fresh air at a time when the bulk of British Christianity was inconsequential. Although he bought in, at least on the surface level, to the prevailing Self-Help individualism of his day, the heart of his theology was relational. The two aspects of his character proved to be mutually modifying, and the end product was a deep concern for the souls of individuals, for the purpose of seeing them share in the joy of communing, first and foremost with Christ Himself as regenerate persons, and then consequently with His people as persons grafted into the community in whom His presence dwells. His fondness for the ordinance of communion makes sense is this light: it serves as a concrete reminder (Spurgeon often referred to it more emphatically as a “forcible reminder”) of the most unknowable mysteries of the Christian faith—most notably, of the atonement.

Thus, for Surgeon the value of the Communion ordinance was not respectful adherence to the ancient wellspring of Christian tradition, something with which he had a complex and uneven relationship, but instead the impossibility of separating the symbols of the bread and wine from the reality of the pierced flesh and flowing blood of the once wounded and eternally present savior. Here what Peter J. Morden has dubbed “Spurgeon’s convertive piety” was at work, and the frequent, attentive observance of Communion was an apt tool in the life of the believer to further cement their self-understanding in the concrete imagery of the gospel. Its effects on the community that observes the ordinance together are equally dramatic. It is in the daily “feasting on the Lord” in the form of spiritual disciplines and surrender to the guidance of the Holy Spirit that individuals are “conformed to the image of Christ; enjoyed together at the “Lord’s table,” individuals who are growing in godliness actualize the realities that define them as a community.

“Feasting on the Lord” together is, for Spurgeon, the most tangible discipline whereby a collective church community can commune with Christ. The intimacy with which they commune with God is illustrated by the intrusive nature of the ordinance: the elements are taken into the body, and so the Christ whom they portray is invited for all time into the whole person of the recipient. Receiving the elements into our persons together knits us to one another as brothers and sisters united by our common identity as people indwelt by Christ. Our kinship is more than skin deep. This likewise illuminates the experiential nature of Spurgeon’s theology. It is not merely a common adherence to an external tradition, but the common experience of the crucified Christ who is testified to in the elements that shapes us as a community. Thus, what initially appears to be a typically Victorian individualism proves, in fact, to be a humble reverence to the reality of experience. Whereas common Church practice, both among the establishment churches that sometimes derived harmony coercively through an imposition of the sacred rites onto individual believers and nonconformist churches that often lost their sense of Eucharistic identity in their zeal to distance themselves from sacerdotalism, Spurgeon’s robust integrative motif produced a clearly Evangelical understanding of the ordinance that, while nearly identical in substance to the traditional Baptist memorialist position, was decidedly more alive.

The same motif that formed his Eucharistic orthodoxy gave shape to his praxy. Plenty has been written about the seemingly tireless work that he would carry out on a daily basis. He was once asked, “how is it that you do the work of two men in a day?” He was reported to have wryly smiled and responded, “Have you forgotten that there are two men?” When his writings are closely examined, it becomes clear that this was not merely a clever quip. It was a summary of his whole attitude toward ministry. He was speaking in individualistic terms here, as the situation demanded, but it is also illustrative of his understanding of the ministry of the local church as well.

It should be noted early on that Spurgeon had a comparatively weak ecclesiological stance. He was indeed a fairly paint-by-numbers particular Baptist in regard to his congregationalism, but he approached ministries (such as the ordinance of communion) that were generally understood to be offices reserved for the local church with a looseness that was largely unheard of in Baptist life. Therefore, it is with his characteristic looseness that he espoused a paradoxically robust theology of ministry in which the Church labors away in the world as witnesses to the mercy of God as co-laborers with Christ. Informed largely by his Fullerite Calvinism, he conceptualized the Christ with whom believers commune not as an “absentee savior” but as an active worker in and alongside the Church whom He created. Although the nature of Christ’s labor alongside the Church was functionally different, it would have been inconceivable to Spurgeon to imagine that He was not actively working in the world to prepare hearts to meet Him and to prepare the way for His return.

For Spurgeon, this inevitably included the reformation of society. Although he was not a political radical, he saw the necessity of seeking relief for the suffering of those crushed under the heel of contemporary society’s protracted power struggles. This included slaves, underpaid laborers, the uneducated poor, indigenous natives of lands imperialized by the West, and soldiers wielded as disposable weapons by feuding governments. He felt he could not commune with Christ faithfully if he did not seek to live out the will of Christ in his own life and make it a reality in the lives of the downtrodden. It was, then, faithfulness to the principles of the gospel that Christ came to actualize that motivated Spurgeon to shepherd the church bodies over whom he had influence into unprecedented social concern. Sharing in the work of Christ was a concrete embodiment of the blood bought communion with him that believers enjoyed.

This led, as was mentioned above, to a multitude of different outworkings. The most relevant of these is The Pastor’s College a seminary aimed at preparing young, poor ministers for a future of ministry after Spurgeon’s own vision. It was not to create an army of minions who would then crowd out the London Church scene to give him a unique cultural hegemony. Rather, it was to extend the scope of his vision past the immediate influence of the Metropolitan Tabernacle. Although the ministries in which they had involved themselves were going exceptionally well, there was an obvious need for fellow churches to join in the work. The need was not only practical but theological. Communing with Christ was not simply the business of the people of the Metropolitan Tabernacle, but the business of the whole Church. Therefore, Spurgeon sought to pave the way for future ministers to take up the mantel that his congregation had thus far carried on its own.

It was an obvious outworking of his theology that the people who communed with God must commune with one another in the process of communing with God. This meant quite plainly that he had a responsibility to bring the mission of Christ within reach for other Churches. Although there was plenty to be done for and with stagnant churches during his life, he found his primary role in the process to be the training of low-income pastors. He was noted to have suggested that “If God has a preference for one group of people over others, it is the poor whom he favors … and we are blessed to favor them as well.” One of the requirements of The Pastor’s College was to live with a working-class family from the Metropolitan Tabernacle to become acquainted with the conditions of life faced by working-people. It was of no use to anyone, Spurgeon thought, if the clergy was to be composed entirely of cultural elites whose sermons are aimed at furthering their own respectability and whose personal concerns are at odds with the radical inclusiveness of the gospel message brought to the Church by Christ.

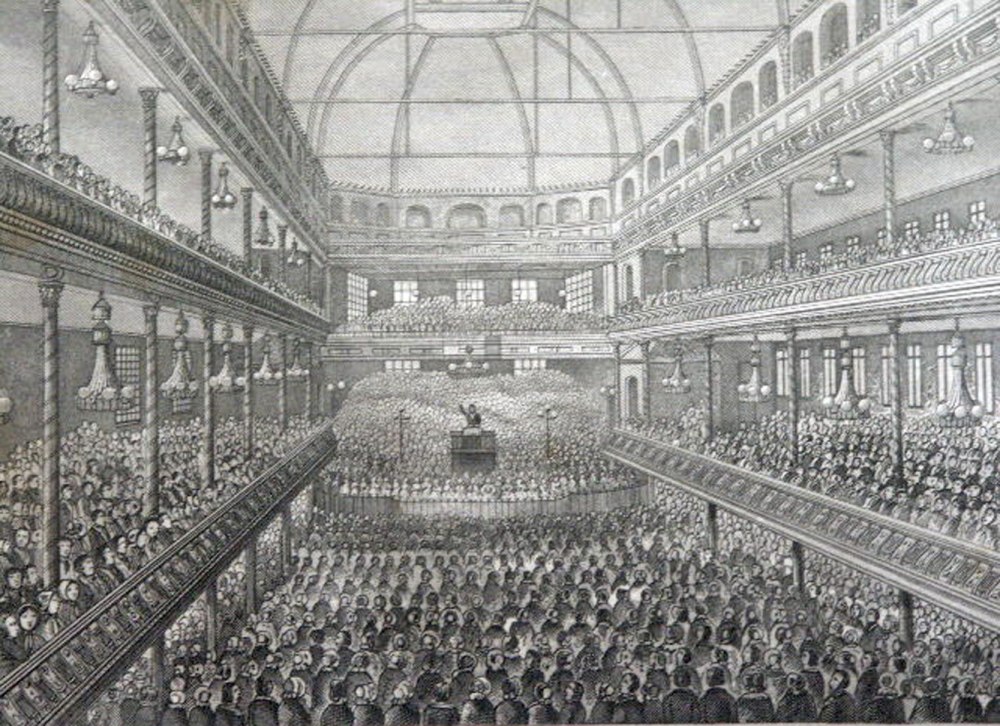

As a result, Spurgeon’s disciples made up the majority of Baptist church-planters by a wide-margin during the second half of his lifetime—congregations with a driving compassion for the working-class and a robust adherence to the Calvinistic doctrines of grace. In the troubling absence of lively churches with whom to share in the discipline of communing with Christ in mutual gospel labor, he prepared leaders to plant a whole slew, and in doing so recast the direction of nonconformism for future generations of devout Brits. Likewise, and equally important, the multiplying activity of the Metropolitan Tabernacle went a long way in overcoming lostness in Victorian London. As they colabored with Jesus against the evils of false religion, irreligion, and social oppression, souls were redeemed at an alarming rate. Throughout the entire process, he was sure to center the spiritual development of the students around his own integrative motif, often illustrating their collective identity as blood-bought people by celebrating the ordinance of communion after Friday lectures.

And he prayed for them. It was his conviction that the labor which they had been called to carry out alongside the tireless Jesus was possible only through continued mutual prayer support. Charles no more believed that he could accomplish notable things for Jesus on His own strength than that he could cross the Atlantic Ocean on horseback. The same was true, he reasoned, for all ministers. Therefore he urged his students and congregants to “pray [for him] without ceasing],” that he might be an effective minister of the gospel in their city and in the world. One of the many “possibly apocryphal” Spurgeon stories that I mentioned in the first entry of this series involved someone visiting the Metropolitan Tabernacle on one of the rare nights in which there was not an organized activity going on, having scheduled an interview with the pastor. When they arrived, they were greeted warmly and personally given a tour by his interview subject. “What is the secret to your church’s success?” They asked. He smiled thoughtfully and said, “follow me,” before taking them into a sequestered room that was filled with people praying together for the church, for Spurgeon, for missions, etc. Charles looked at them earnestly and insisted, “what you are looking at is the life-blood of our Church.”

In another, more easily verifiable instance, a vacationing Spurgeon was asked about his ministry strategy by a local pastor from Mentone. After stewing on it for a few moments, he replied, “my people pray for me.” Communing with Christ entailed spending time with Him in prayer in the same way that you would spend time with another person. It was not for Spurgeon merely a tool whereby God could be made to act in the believer’s favor, nor should it consist in what he saw as monotonous prewritten mantras lifted up to the heavens for the sheer sake of tradition. He saw prayer in largely the same terms as his American contemporary, E.M. Bounds: personal prayer was the most relational of all spiritual disciplines, given that it consists from beginning to end in intentional time spent basking in the presence of the risen Christ and sitting at His feet. Although its primary function is not the sanctification of the believer, it is the inevitable product. One cannot sit at the feet of Jesus without being changed by what He has to say.

Likewise, one cannot be delighted by the treasures of knowing Christ intimately without experiencing a fundamental change in the underlying desires that drive their decisions, both moral and practical. Prayer was God’s chief means of sanctification, and per His divine scheme, sanctification was the product of a sustained and soul-sustaining friendship with Jesus.

The sanctifying properties of prayer work horizontally as well as vertically. It was not merely devotional prayer that sustained the prince of preachers, but intercession that had been lifted up on his behalf. In Spurgeon’s theological framework, God predestined not only events but the petitions that brought them about. He saw no contradiction between his determinism and his steadfast devotion to prayer. He could therefore comfortably teach that nothing happened for the kingdom apart from the prayers of the saints while simultaneously teaching that God’s sovereignty covered every aspect of existence, including salvation history. The conversion of a single sinner, for example, could be attributed to the ceaseless prayers of his wife and mother on his behalf, which they lifted up because God had willed the man to be saved. His theology presupposes that God has established an order in which He rarely carries out His own will unless He is asked. Therefore, He metes out understanding to different individuals in the Church so that they might petition Him to carry out His desires. “God predestines our prayers,” Spurgeon was known to say.

This played out vividly in his understanding of ministerial success. As he grew more experienced, he placed a steadily increasing emphasis upon congregation-wide prayer meetings. It became his conviction that his preaching, however important, was of less concrete value than the mutual prayers off the people in his congregation lifted up for one another. He would preach to them sometimes five days a week, but he wanted even more desperately for them to pray for one another (and for him). In this way, communing with Christ in prayer did much of the work of bringing His people into communing with one another. It is not a stretch to suggest that the tightly-knit community that formed around the shared communion with Christ in these congregational prayer meetings became a catalyst for the groundbreaking work that God entrusted to them throughout the nearly four decades of Spurgeon’s pastorate. Indulging together in communion with Christ through prayer ennobled them to follow through in communion with Christ in the mission field and on the streets of London. The resultant church was a prophetic force to be reckoned with in a Christless culture that had hitherto come to justify its idolatry by posturing itself as Christendom.